The sun peeks through the clouds in the dusty town of Amarillo, Texas, as a young boy steps inside Rogers Elementary. With a backpack slung over his shoulder and books held close to his chest, he walks to his third-grade classroom. Patiently, he stands outside the door waiting for the sound of the first school bell.

When it rings, he knows he gets to enter Whitney Harris’ classroom—a place that has deeply impacted his life.

The child is a refugee from Ethiopia and has been in the United States for just two years. Scars cover his body from the violence he endured in Ethiopia. He has suffered more emotional trauma from war that any child ever should.

When he was first assigned to Harris’ classroom in 2010, he had serious behavioral issues. “He fought all the time and was always getting into trouble,” Harris says.

To help redirect the boy’s attention, Harris worked hard to set up a safe environment for him. “I tried to make sure our day was filled with music, laughter, engaging work with just the right amount of scaffolding, and of course, learning.”

She set up clear boundaries for him, but also gave him some freedom. After the first six weeks of school, she saw a big shift in him that was related to these factors, but also to creativity. Harris exposes her students to various artists such as van Gogh, Picasso, Michelangelo, and da Vinci, and then gives them the opportunity to create in their styles. “By studying these artists, he was exposed to fine arts and was able to experiment and be creative through art.”

“I created a place where he felt safe and was happy,” Harris says.

This young boy is not the only child to flourish in Harris’ classroom. She’s had a positive impact on many kids, from a variety of different backgrounds.

For the last four years, the inspiring teacher has dedicated her life to teaching low-income, immigrant, and refugee children at Rogers Elementary in northern Amarillo. At the school, 10 languages are spoken and 90 percent of the students live below the poverty line. In her third-grade classroom, 75 percent of the students are ESL learners.

Amarillo and the Refugee Crisis

At Rogers Elementary, and other neighboring schools, the refugee population is high. This is because each year in Amarillo, approximately 1,000 refugees are resettled after fleeing persecution, violence and political strife in war-ravaged countries such as Somalia, Myanmar, and Iraq. As Harris says, “Most come here looking for a better life.”

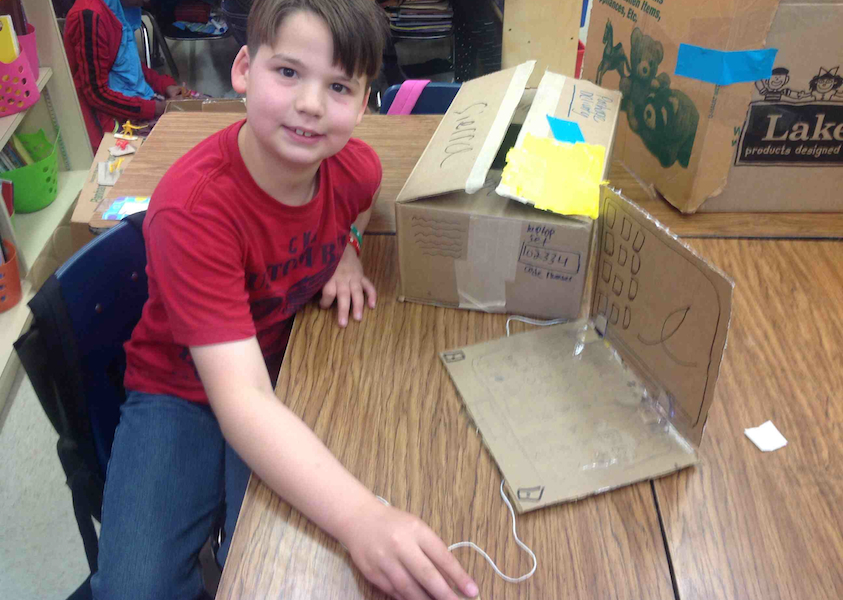

Three third graders from different backgrounds work together during the 2013 Global Cardboard Challenge at Rogers Elementary School. (Photo c/o Whitney Harris)

Amarillo isn’t alone in resettling refugees. In 2013, 98,400 refugees were resettled in 21 countries, according to The UN Refugee Agency.

This number is small compared to how big the refugee crisis actually is. In the world today, The UN Refugee Agency reports that there are more than 50 million refugees, asylum-seekers and internally displaced people—and half are children. This number is the highest it has been since World War II.

For the majority of these families, life is restricted to the confines of a barbed-wire enclosed refugee camp. For the few that get to resettle, a different yet difficult journey awaits. Work is typically limited, the culture is quite different, and language is a major barrier.

In Amarillo, a city that receives a higher ratio of new refugees to the existing population than any other Texas city, the draw is a large meatpacking plant where they don’t need to speak much English.

To ease the transition upon arrival, The Refugee Services of Texas and Catholic Charities of the Texas Panhandle help to provide adults with these jobs, a place to live, basic necessities, medical care, English education, and school enrollment for their children.

Before coming to America, the majority of refugee kids were never taught English and had little to no formal schooling.

“We take for granted speaking the same language when having a conversation and teaching,” Harris says. “Simple requests are not understood, let alone teaching curriculum. However, refugee children are quick learners and very resilient and most want to learn English, which truly helps.”

The language barrier, Harris adds, is why she is adamant about making time in her classroom for creativity.

Creativity Breaks Down Barriers

“Giving students the opportunity to explore their interests and demonstrate their learning through a creative task,” she explains, “takes a lot of pressure off refugee students because it doesn’t have to be a written or spoken response.”

It makes taking risks easier and helps give them confidence.

As it did for a Burmese child who had been in Amarillo for just over a year. The third grader spoke very little English and was in the early stages of writing. However, just because he couldn’t write or speak English very well didn’t mean he didn’t have things to communicate.

This was especially apparent one day during the class’s writing workshop. After a discouraging attempt to write, he put his face down, gripped his pencil, and began to draw a beautiful and detailed picture of himself and other children playing baseball at the refugee camp where he stayed before coming to Amarillo.

“You could see the barbed wire fence surrounding the field, tents in the background, mountains in the distance, and his country’s flag flying at the top of the fence. Though he couldn’t talk to me about his thoughts and memories, through his amazing artistic ability, I could begin to understand,” Harris says.

When her students are given the chance to be creative, they are problem solving and gaining an understanding of who they are. They’re learning how to communicate with others, how to ask for help, and how to share their ideas.

Much of the time, this takes place in Harris’ classroom during Genius Hour, a movement making waves at schools across the country. For one hour a week, kids are free to unleash their creativity and explore their passions.

In Harris’s class, Genius Hour takes place on Monday afternoons and helps set the tone for the week. “They love getting time to investigate and explore things that really interest them and it has also helped to build a community in our classroom,” she says.

The students study different artists throughout the year, and during Genius Hour, they are free to paint, sculpt, and draw in the style of their favorite painters, who they learned about in class. The third graders are also free to tackle other projects that interest them. For example, one student designed her own lemonade stand and another designed his own math book, fully equipped with problems for his fellow students to solve.

Last October, they spent several Genius Hours planning, collaborating, and building cardboard creations as part of the 2013 Global Cardboard Challenge.

Students made all kinds of things, including a car that self-destructs and a personal laptop.

A student displays his cardboard laptop, complete with mouse, plug and even a company to go along with it, during the Cardboard Challenge. (Photo c/o Whitney Harris)

“Just watching them learn to work together and to share was pretty huge,” Harris says of her students during the Cardboard Challenge. “They were so engaged and loved every minute of it. It was kind of like they never had this opportunity before.”

The Cardboard Challenge, and the class’s other creative tasks, help to show all of her students, especially the ones who once struggled to survive, that anything is possible. When you give kids the chance to use their talents, Harris says, they simply shine.

(Top Photo by Si Griffiths (Own work), via Wikimedia Commons)

Join ‘Got Genius?’ The Google Hangout on Genius Hour

In May, we shared our first story on the Genius Hour movement, featuring the adventures of Ms. Joy Kirr and her seventh graders in Arlington Heights, Illinois. This month, join us for a frank discussion with Joy Kirr, Gallit Zvi and other Genius Hour teachers about the joys, hazards and epiphanies that come with putting kids and their passions in the driver’s seat. The Google Hangout will broadcast live on Thursday, July 24, 3 pm PST / 6 pm EST. Tune in here (and share your questions via G+’s Q&A feature).

This story was written by Jenny Inglee, the Imagination Foundation’s Imagination Curator and The Storybook Editor. The first collection of stories in The Storybook focus on the work of inspiring individuals, schools, and organizations that participated in the 2013 Global Cardboard Challenge.

Recent Comments