Did you know that Nobel laureates in the sciences are 25 times more likely than other scientists to sing, dance, or act? That they are 17 times more likely to be a visual artist, 12 times more likely to write poetry and literature, and four times more likely to be a musician?

Take, for example, Alexander Graham Bell. He may be known for inventing the telephone, but he was also a talented pianist. In fact, it was his understanding of pitch and chords that helped him create the world-changing device responsible for connecting billions of people across the globe.

Or how about Alexis Carrel, a surgeon who utilized his knowledge of lace making to invent the stitching technique used in open-heart surgeries.

These life-altering inventions are just two examples of what can happen when the arts and sciences converge. As leading MacArthur Fellow Robert Root-Bernstein says, “Arts don’t just prettify science or make technology more aesthetic; they often make both possible.”

Schools like the new K-6 Knox Gifted Academy in Chandler, Arizona recognize the power of this convergence between the arts and sciences. Knox is designed to inspire innovation and excellence through STEAM, a teaching framework that brings the A for the arts into STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math).

Georgette Yakman, a teacher and innovator who helped bring the acronym STEAM into the mainstream, explained its power at the Big Ideas Fest in 2011. She said:

STEAM “connects the different subjects together in the way they would relate to the business world and to each other.”

If we look at Apple as an example, the technologies behind products like the Macintosh computer, iPhone, and iPad set a precedent, and so did the designs. “It’s in Apple’s DNA that technology alone is not enough. It’s technology married with liberal arts, humanities that yields us the result that makes our heart sing,” Steve Jobs explained in 2011, according to CNET.

With STEAM, kids are learning the value of merging art and science early in their lives.

Michael Buist, a 16-year teaching veteran and one of Knox’s founding educators, shares how this works at his school.

During the school day, he says, teachers practice an interdisciplinary approach to education and try to make the integration of the arts and sciences “seamless.”

Buist’s fifth graders, for example, recently read a book titled ‘Out of Mind‘ by Sharon Draper. The story is about a girl with cerebral palsy who has a photographic memory and experiences synesthesia. When the child hears music, she sees all types of colors.

Buist wanted his students to relate to what the heroine in the story was going through, so he played several different songs and had his students match colors, textures, and brush strokes to each tune. Here, he was integrating art, music, and language arts into one lesson.

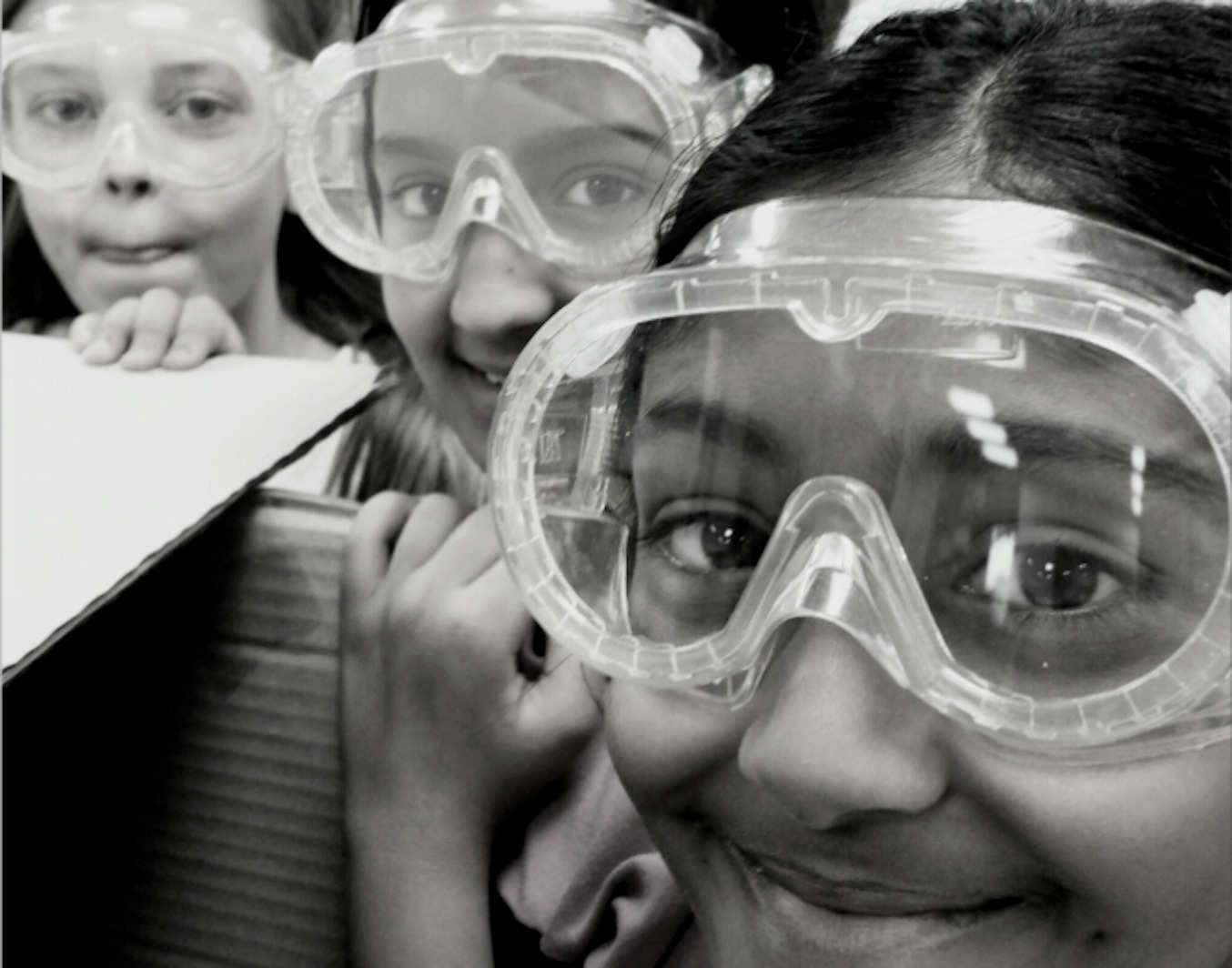

Another example of Knox’s commitment to STEAM was the school’s participation in last year’s Global Cardboard Challenge.

Fifth graders at Knox used the engineering design process to create a Pac-Man game during their Cardboard Challenge. (Photo c/o Michael Buist)

Over the course of a few weeks, Buist and the other teachers leading the Challenge, Jennifer Nusbaum and Albert Notley, encouraged students to think about how they could connect this event to their lessons on force and motion and simple machines. Next they were tasked with thinking about how their creations could relate to their language arts, reading, and math assignments.

The E (engineering) and M (mathematics) part of STEAM, Buist says, played a part in the design process. The students had to create a blueprint of what their project was going to look like. In doing this, they also needed to think mathematically. They had to figure out how big it was going to be, if they were going to make a model or something full size, and how much cardboard they would need.

A student project that stood out to him, and successfully incorporated all these elements, was a bowling alley manufactured from cardboard and other recycled materials.

It started out as simply a lane and some pins, but the students’ idea quickly grew into something much more elaborate. Together, the group created a ball return, manual pin sweeper, scoreboard, and a leaderboard.

Not only did the kids utilize their knowledge of math and science, but they brought to life intricate details of their creative vision, all the way down to a pair of cardboard bowling shoes.

Girls work on their bowling alley. The pins are made out of cardboard, Starbucks lids and egg cartons. (Photo c/o Michael Buist)

Other kids who participated in the Cardboard Challenge made a flute and a viola, an animated space-themed photo booth, and a colorful DNA helix.

Buist said it was powerful to witness the energy and inventiveness that took place during the Challenge. Three classrooms that are typically separated were wide open, and cardboard creations were strewn across the floor. The kids’ parents even came out to play and for just a little while they—and the teachers—allowed themselves to get lost in their children’s world of wonder.

It was STEAM in action: the perfect example of how art merged with science can bring a child’s imagination to life.

Join our Imagination Twitter Chat on STEAM with special guests Jessica Lahey, writer for ‘The Atlantic’ and ‘The New York Times,’ and Christine Mytko, Bay Area maker/teacher extraordinaire. Check out Jessica’s article, ‘STEM Needs a New Letter’ and join us on Thursday, June 12, Noon PST / 3pm EST to talk STEM, STEAM and educating beyond the acronym. #TheStorybookChat

This story was written by Jenny Inglee, the Imagination Foundation’s Imagination Curator and The Storybook Editor. The first collection of stories in The Storybook focus on the work of inspiring individuals, schools, and organizations that participated in the 2013 Global Cardboard Challenge.

[primary_link_alt text=”Sign me up for The Storybook” href=”https://eepurl.com/MDElb” style=”margin-left: 0;”]

Recent Comments